In the year 1506, amidst the lush vineyards of ancient Rome, one of the most celebrated sculptures of the ancient world was unearthed. This masterpiece, known as the Laocoön Group, has since captivated art enthusiasts and historians alike with its dramatic portrayal of human suffering and its extraordinary artistic execution. Now residing in the hallowed halls of the Vatican Museums, the Laocoön Group continues to be a focal point for those seeking to unravel the mysteries of the past and appreciate the enduring power of art.

The Discovery and Early Fame

The discovery of the Laocoön statue was a momentous event that sent shockwaves through the art world. It was found in the vineyard of Felice De Fredis near the Basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore, and upon learning of the find, the esteemed Pope Julius II quickly dispatched Michelangelo and other prominent artists to examine the statue. Recognizing its immense value, the Pope swiftly acquired the statue and placed it in the Vatican, marking the beginning of its illustrious public display.

The Sculptors and Their Creation

The Laocoön Group has been attributed to three Greek sculptors from the island of Rhodes: Agesander, Athenodoros, and Polydorus. This attribution comes from the renowned Roman writer on art, Pliny the Elder, although he did not specify the exact date of the statue’s creation. Scholars have long debated whether the Laocoön Group is an original work or a Roman copy of an earlier Greek bronze, with the prevailing consensus being that it exemplifies the Hellenistic baroque tradition.

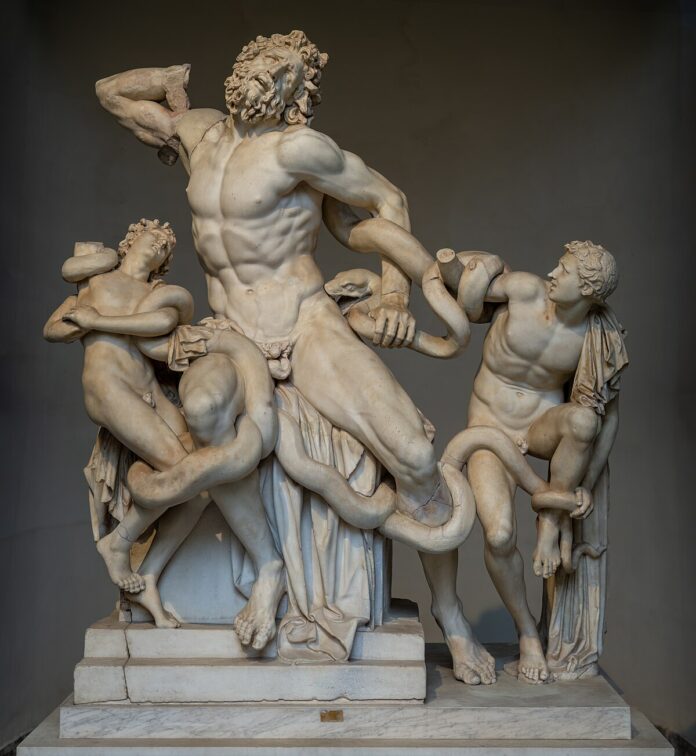

The Agony of Laocoön

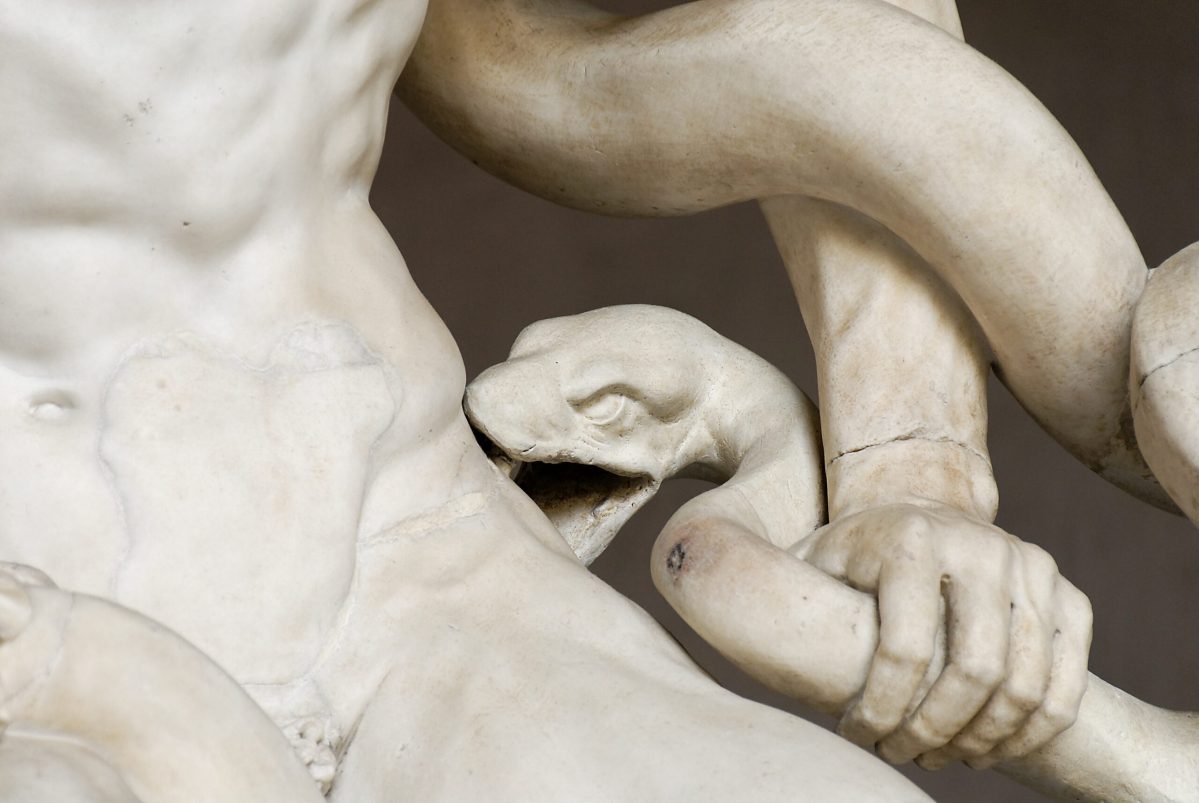

The statue depicts the tragic figure of Laocoön, a Trojan priest, and his sons, Antiphantes and Thymbraeus, ensnared by the coils of sea serpents. The nearly life-sized figures convey a profound sense of human agony, devoid of any redemptive narrative common in Christian art. Laocoön’s contorted expression, with his bulging eyebrows, reflects a raw and intense suffering that has been noted by scholars as physiologically impossible yet emotionally powerful.

The Laocoön Group is widely regarded as a pinnacle of the Hellenistic baroque style, characterized by its dynamic composition and emotional intensity. Despite its Greek origins, the statue likely adorned the home of a wealthy Roman, possibly even within the Imperial family. The proposed dates for its creation range from 200 BC to the 70s AD, with the Julio-Claudian period being the favored timeframe.

The Story of Laocoön

The tragic tale of Laocoön has been retold across various ancient sources, with differing accounts of his fate. In Virgil’s “Aeneid,” Laocoön, a priest of Poseidon, is punished with his sons for trying to expose the ruse of the Trojan Horse. In Sophocles’ lost tragedy, Laocoön is depicted as a priest of Apollo, punished for breaking his vow of celibacy. These varying narratives reflect the moral ambiguity of Laocoön’s suffering, which has been a subject of ongoing scholarly debate.

Restorations and Modifications

Over the centuries, the Laocoön Group has undergone various restorations and modifications. When the statue was first discovered, it was missing several parts, including Laocoön’s right arm. Michelangelo and other artists debated the correct positioning of the arm, leading to different restorations over time. Notably, a bent arm discovered by Ludwig Pollak in 1906 was eventually recognized as the original and reattached in 1957.

Influence on Renaissance and Baroque Art

The Laocoön Group’s dramatic portrayal of suffering had a profound impact on the art of the Renaissance. Michelangelo, deeply influenced by the statue, incorporated similar emotional and physical intensity in his own works. Other renowned artists, such as Raphael, Titian, and Rubens, also drew inspiration from the Laocoön, reflecting its enduring legacy in Western art.

Academic and Cultural Debates

The Laocoön Group has sparked extensive academic debate regarding its artistic and cultural significance. Scholars such as Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, and others have explored the statue’s portrayal of beauty amidst agony. Meanwhile, critics like William Blake and John Ruskin have offered their perspectives on the statue’s naturalism and emotional impact, contributing to the ongoing discourse on its place in art history.