The history of ancient Greek coinage can be categorized into four distinct periods: the Archaic, Classical, Hellenistic, and Roman periods. The Archaic period spanned from the introduction of coinage to the Greek world in the 7th century BC until the Persian Wars around 480 BC. Following this, the Classical period emerged and lasted until approximately 330 BC, when Alexander the Great’s conquests marked the beginning of the Hellenistic period. The Hellenistic period extended until the Greek world was absorbed by the Romans in the 1st century BC. Even under Roman rule, Greek cities continued to mint their own coins for several more centuries. These coins, produced during the Roman era, are commonly referred to as Roman provincial coins or Greek Imperial Coins.

Archaic period (until about 480 BC)

The earliest known electrum coins, which were discovered under the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, are estimated to date back to around 640 BC [7]. These coins were likely issued either by the non-Greek Lydians for their own transactions or by Greek mercenaries who preferred to receive payment in precious metals at the end of their service and wanted a way to authenticate their earnings. Electrum, an alloy of gold and silver, was highly valued and abundant in the region, making it a suitable material for these early coins.

In the mid-6th century BC, King Croesus introduced coins made of pure gold and pure silver, known as Croeseids [7]. Herodotus credits the Lydians with the invention of pure gold and silver coinage, as they were the first to use these metals as currency and engage in retail trade [8].

The Greek world comprised over two thousand self-governing city-states, and a majority of them issued their own coins. Some of these coins, such as the silver stater or didrachm of Aegina, gained wide circulation beyond their originating polis, indicating their use in inter-city trade. These Aeginetan coins were commonly found in hoards in Egypt and the Levant, regions that lacked a sufficient supply of silver. As these coins gained popularity, other cities began to mint their own coins following the Aeginetan weight standard of 6.1 grams (3.9 dwt) per drachm, often incorporating their own symbols.

However, Athenian coins, known as “owls” due to their central design feature, were struck on the “Attic” standard, with a drachm weighing 4.3 grams (2.8 dwt) of silver. Athens benefited from its abundant silver supply extracted from the mines at Laurion and its growing dominance in trade, establishing the Attic standard as the prominent one [9]. The coins minted in Athens adhered to a strict standard of purity and weight, contributing to their success as the primary trade currency of the era. Tetradrachms, following this weight standard, remained widely circulated and often served as the most commonly used coin throughout the classical period. During the time of Alexander the Great and his Hellenistic successors, these large denomination coins were frequently employed for substantial payments or hoarding purposes.

International circulation

Archaic Greek coins had extensive circulation within the Achaemenid Empire [10]. They were discovered in coin hoards throughout the empire, such as the Ghazzat hoard and the Apadana hoard. These coins were also found in regions far to the east, including the Kabul hoard and the Pushkalavati hoard in ancient India, following the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley. The presence of Greek coins, both Archaic and early Classical, is significantly more abundant in Achaemenid coin hoards in the eastern parts of the empire compared to Sigloi (Persian coins), indicating that Greek coinage played a central role in the monetary system of those regions [10]. This suggests that Greek coins were widely accepted and used in trade and commerce within the Achaemenid Empire.

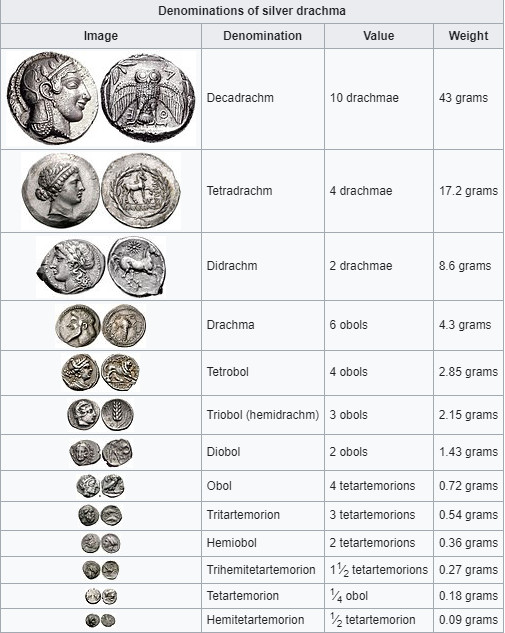

Weight standards and denominations

The ancient Greek monetary system was defined by three significant standards: the Attic standard, the Corinthian standard, and the Aeginetan standard. The Attic standard was based on the Athenian drachma, which weighed 4.3 grams (2.8 pennyweights) of silver. The Corinthian standard used the stater, weighing 8.6 grams (5.5 dwt) of silver, which was further divided into three silver drachmas weighing 2.9 grams (1.9 dwt) each. The Aeginetan standard utilized the stater or didrachm, weighing 12.2 grams (7.8 dwt), with a drachma weighing 6.1 grams (3.9 dwt).

The term “drachma” derives from the Greek word meaning “a handful” or “a grasp,” suggesting that in pre-coinage times, spits (pointed rods) were used as units of measure in daily transactions. These spits were divided into six obols, with six spits forming a “handful.” This indicates that prior to the introduction of coins in Greece, spits may have served as a form of transportable bullion, particularly iron, highly valued for manufacturing durable tools and weapons. Over time, the use of precious metals became more prevalent but also more cumbersome compared to the earlier iron spits.

Interestingly, Spartan legislation famously prohibited the minting of Spartan coins and mandated the use of iron ingots known as pelanoi instead. This measure aimed to discourage avarice and the accumulation of wealth. In addition to its original meaning, the term “obol” (ὀβολός or ὀβελός) continued to be used in Greek to refer to coins of small value and is still used in Modern Greek slang (όβολα, óvola) to denote “monies.”

The obol, in turn, was further divided into tetartemorioi (singular tetartemorion), which represented 1/4 of an obol or 1/24 of a drachm. This particular coin, noted by Aristotle as the smallest silver coin, was minted in Athens, Colophon, and other cities [5]: 237 . Additionally, various multiples of this denomination were also produced, such as the trihemitetartemorion, which was valued at 3/8 of an obol [5]: 247 .

Classical period (480–323 BC)

During the Classical period, Greek coinage achieved a remarkable level of technical and aesthetic excellence. Major cities began minting high-quality silver and gold coins, often featuring portraits of patron deities, legendary heroes, or symbols representing the city. Some coins incorporated visual puns, such as the rose on Rhodes coins, referencing the Greek word for rose, “rhodon.” Inscriptions on coins also became more common, typically indicating the issuing city.

The wealthy cities of Sicily, in particular, produced exceptionally fine coins. The large silver decadrachm, a 10-drachm coin, from Syracuse is widely regarded as one of the finest coins ever produced in the ancient world. Syracusan coins usually depicted the head of the nymph Arethusa on one side and a victorious quadriga (a four-horse chariot) on the other. The tyrants of Syracuse, who were immensely wealthy, sponsored quadrigas for the Olympic chariot race as part of their public relations strategy. Their ability to finance multiple quadrigas at a time resulted in frequent victories in this prestigious event. Syracuse, led by notable engravers like Kimon and Euainetos, became a center of numismatic art during the classical period, producing some of antiquity’s most exquisite coin designs.

Among the earliest centers to mint coins during the Greek colonization of southern Italy (known as Magna Graecia) were Paestum, Crotone, Sybaris, Caulonia, Metapontum, and Taranto. These ancient cities began producing coins between 550 and 510 BC [17][18].

Hellenistic period (323–31 BC)

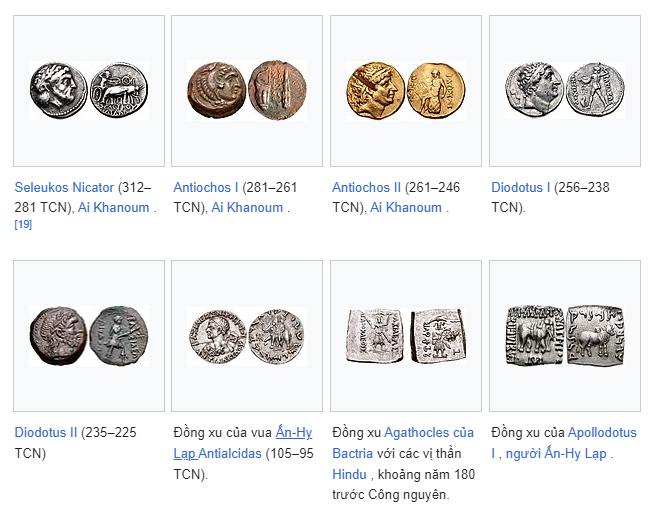

The Hellenistic period witnessed the expansion of Greek culture across a significant portion of the known world. Greek-speaking kingdoms emerged in Egypt, Syria, Iran, and extended as far east as Afghanistan and northwestern India. Greek traders played a crucial role in spreading Greek coins throughout this vast region, and the newly established kingdoms began minting their own coins.

Due to the larger size and wealth of these kingdoms compared to the classical Greek city-states, their coins were often more mass-produced and larger in size. Gold coins became more prevalent during this period. However, these coins generally lacked the aesthetic refinement and delicacy of the earlier Greek coins.

The focus of Hellenistic coinage shifted from the artistic mastery seen in the Classical period to a more standardized and utilitarian approach. Coins became tools of political propaganda and instruments for asserting the power and authority of the ruling monarchs. The images on these coins often depicted the portrait of the ruling king or queen, along with symbols associated with their kingdom or dynastic lineage.

While the artistic quality may have declined in some respects, Hellenistic coins played a significant role in facilitating trade and commerce across the vast territories under Greek influence. They served as a unifying element, representing a common currency that facilitated economic transactions within and between these Hellenistic kingdoms.

Minting

Greek coins were crafted by hand, rather than using modern coin minting machinery. The process involved carving the designs for the front (obverse) and back (reverse) of the coin into a block of bronze or possibly iron known as a die. A blank disk made of gold, silver, or electrum was then cast in a mold. This blank was positioned between the dies, and the coin maker would strike the top die forcefully with a hammer. This action would imprint the designs onto the metal, creating the finished coin.

Coins as a symbol of the city-state

Greek city-state coins were adorned with distinctive symbols or features, serving as early emblems or badges that represented their respective cities and enhanced their prestige. For instance, the Corinthian stater featured the depiction of Pegasus, the mythical winged stallion tamed by their hero Bellerophon. Ephesus coins showcased the sacred bee associated with Artemis, while Athens drachmas displayed the wise owl symbolizing Athena. Aegina drachmas portrayed a chelone, and Selinunte coins depicted celery, known as “selinon” in Greek. Heraclea coins showcased the legendary figure of Heracles, Gela coins featured a man-headed bull representing the river Gela, and Rhodes coins showcased a rose, known as “rhodon” in Greek. Knossos coins depicted the labyrinth or the legendary minotaur, representing Minoan Crete. Melos coins displayed an apple, referred to as “mēlon” in Greek, and Thebes coins showcased a Boeotian shield.