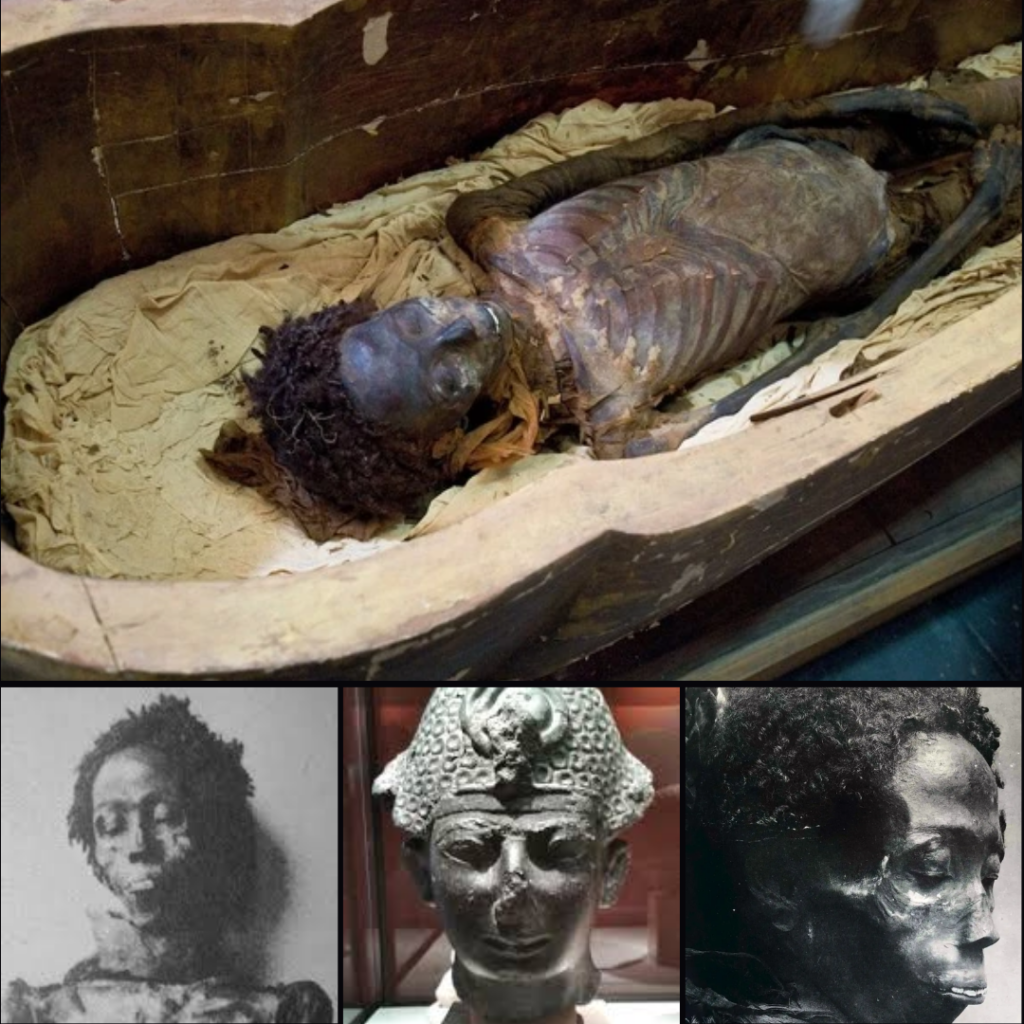

The mummy of Maiherpri is so well preserved that it almost looks like he is in a peaceful sleep. Buried in the Valley of the Kings, his life remains shrouded in secrets. When the mummy was unwrapped on March 22, 1901, Georges Daressy was the first to see his face in centuries. Daressy was struck by the mummy’s remarkable preservation. Upon removing the mummy mask, he revealed the beautiful face of a young man whose features appeared more Nubian than those of other individuals buried in the Valley of the Kings. Although initially unclear whether Maiherpri’s appearance was due to the mummification process or his natural complexion, researchers have since concluded that he must have been Nubian. Victor Loret suggested that these remains belonged to a royal prince from the 18th dynasty.

Victor Loret discovered the tomb of Maiherpri in 1899. Situated between the tomb of Amenhotep II (KV35) and Bay (KV13), this tomb contained many precious artifacts but has not garnered significant attention from researchers. The tomb itself is a small shaft with an undecorated burial chamber, characteristic of other non-royal tombs in the Valley of the Kings. Despite its modest appearance, the tomb’s contents, including the well-preserved mummy of Maiherpri, offer valuable insights into the burial practices and social status of individuals in ancient Egypt.

When Victor Loret opened the tomb, he found the mummy of Maiherpri enclosed within two coffins. However, the body had been robbed in antiquity, with many of the precious jewelry and amulets missing and some equipment broken. Despite this, the number of artifacts discovered was still impressive. Among them were items strikingly similar to those found in the tomb of Yuya and Tuya, the parents of Queen Tiye, the legendary wife of Amenhotep III. This connection suggests a possible association between Maiherpri and the royal family of the 18th dynasty, adding further intrigue to his identity and significance.

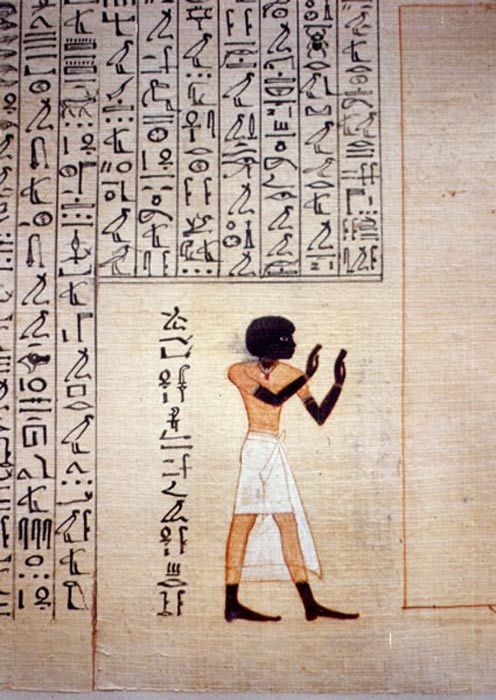

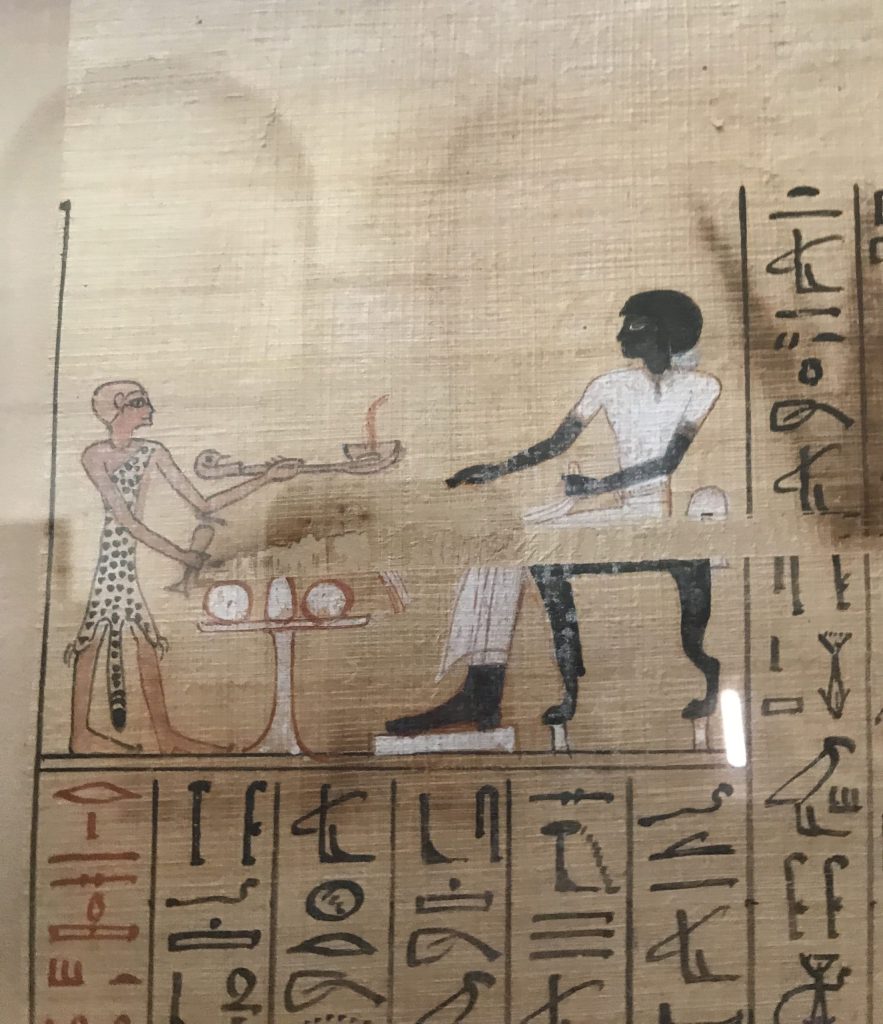

The thieves who entered Maiherpri’s tomb soon after his burial made off with various non-funerary items such as linen, clothing, precious gems, and jewelry. However, many significant artifacts remained untouched, providing valuable insights into ancient Egyptian burial practices and daily life. Among the items left behind were a magnificent papyrus containing an inscription and portrait of the deceased, the Book of the Dead, plant remains, provisions such as bread and meat joints, stone and pottery vessels, a fiancé bowl, seals, dog collars, bracers, arrows and quivers, a game box with gaming pieces, canopic jars and their chest, an Osiris bed, earrings, bracelets, beads, parts of a necklace, amulets, and an embalming plaque. These artifacts offer a glimpse into the religious beliefs, social customs, and material culture of ancient Egypt during the 18th dynasty.

One of the most enigmatic aspects of Maiherpri’s story revolves around the cartouches found in his tomb. A linen winding sheet from the tomb bears a cartouche of Hatshepsut, the famous female pharaoh of the 18th dynasty. However, scholars believe that the tomb itself dates to a later period, adding to the mystery surrounding Maiherpri’s identity and historical context.