The recent discovery of the remains of a man who died 3,000 years ago from a shark attack offers a fascinating glimpse into ancient coastal life. This finding, believed to be the oldest known case of a shark attack victim, was made by archaeologists who analyzed the bones of the victim.

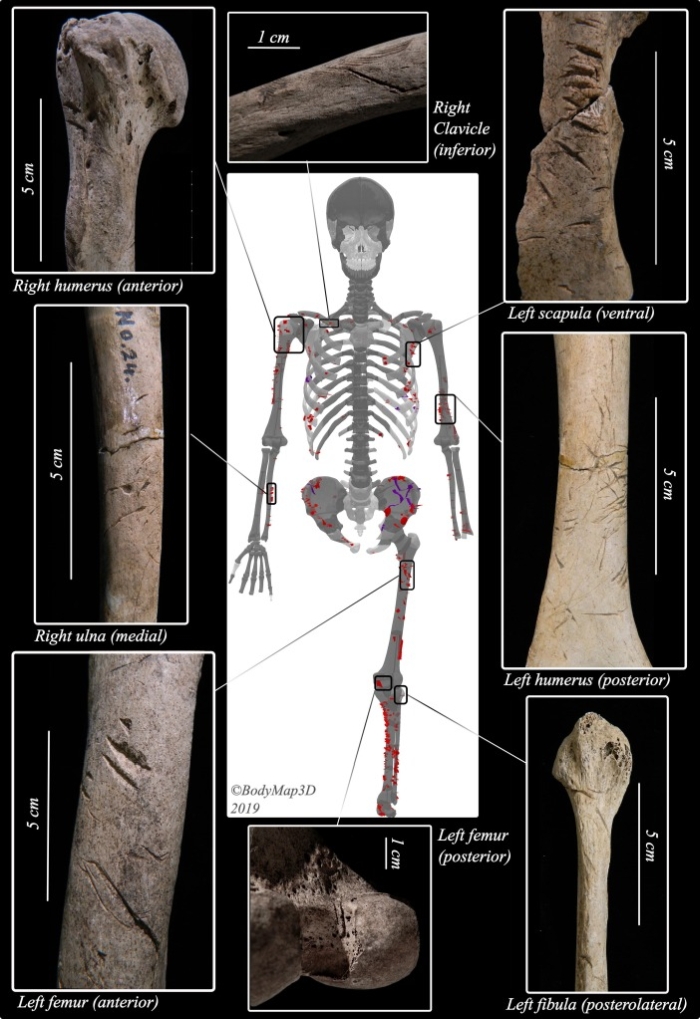

The analysis revealed that the man encountered a shark, one of the ocean’s apex predators, in the inland Seto Sea of Japan. Remarkably, nearly 800 bite marks were recorded on his skeleton, and none of the wounds showed any signs of healing, indicating the confrontation was extremely violent and the man succumbed to the shark attack injuries.

This discovery not only highlights the dangers faced by ancient humans along coastlines but also underscores the formidable presence of sharks in ancient marine ecosystems. The well-preserved remains provide valuable insights into the interactions between humans and marine predators thousands of years ago, offering a unique window into this tragic yet captivating aspect of our shared history.

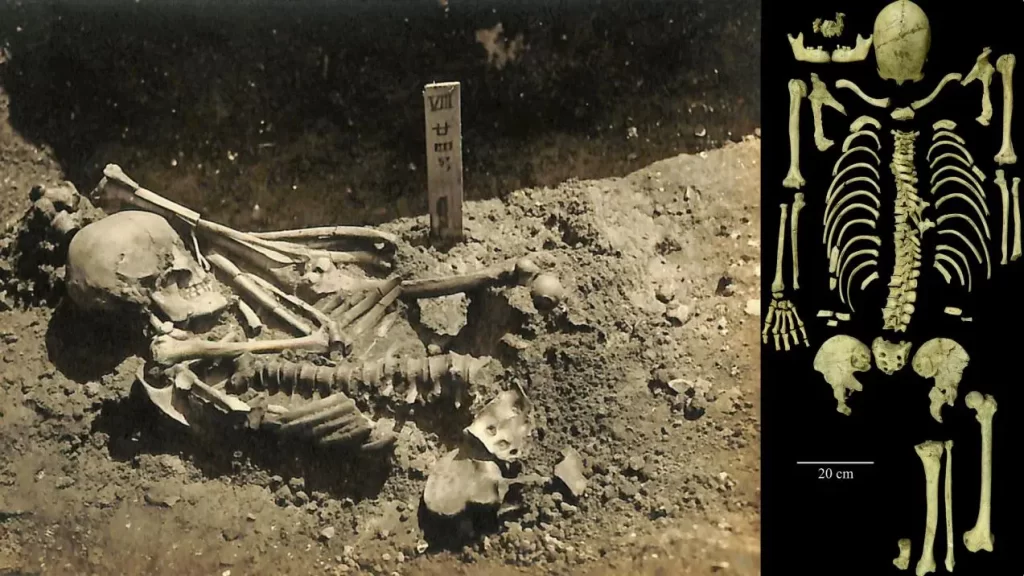

The skeleton, unearthed at the Tsukumo archaeological site near the Seto Inland Sea, has been a subject of study since its excavation in the early 20th century. However, the cause of the numerous injuries to the man’s body has remained unclear until now.

Subsequently, additional bone fragments were discovered by archaeologists Alyssa White and Rick Schults from the University of Oxford in the UK.

The archaeologists stated, “Initially, we were puzzled as to what could have caused at least 790 deep, serrated wounds on this man. There were so many injuries, yet he was buried in the Tsukumo Shell Mound community cemetery. The wounds were concentrated primarily on his arms, legs, chest, and abdomen. Through the analysis process, we were able to rule out interpersonal violence as the cause, and injuries inflicted by a predatory animal seemed the more plausible explanation.”

This latest discovery and analysis of the extensive trauma evident on the remains have provided crucial evidence to support the conclusion that this individual met his demise in a violent encounter with a shark in the ancient maritime setting.

The wounds on the skeleton of the man (designated as Tsukumo No. 24) have aroused curiosity due to their sharp and curved nature. As a result, researchers have concluded that these wounds were not caused by stone tools used during that time. Additionally, the left arm and right leg of this individual were amputated, with the left leg placed over the body in a crossed position during burial.

Shark attacks on humans are rarely documented in archaeological records, but the injuries on this man’s body appear to differ from any encounters with other animal species. Archaeologists have sought the expertise of marine biologist George Burgess from the Florida Museum of Natural History’s Shark Research Program, as well as researched documentation of shark encounters, to consider whether the wounds of Tsukumo No. 24 match those inflicted by shark attacks or not.

Archaeologists Alyssa White and Rick Schults stated, “With these particular injuries, it is clear this man was the victim of a shark attack. He may have been fishing with others at the time, as his body was quickly recovered. Based on the characteristics and distribution of the bite marks, the most likely species responsible are either the tiger shark (Galeocerdo cuvier) or the white shark (Carcharodon carcharias).”

According to the researchers’ analysis, the man was between young and middle-aged at the time of his death, which occurred sometime between 1370 to 1010 BCE. His body was discovered immediately after the shark encounter and was buried in the local community cemetery.

The interaction with the shark appears to have been extremely violent, and the researchers believe the man died relatively quickly. The extensive skeletal trauma, including what appears to be a severed femoral artery, likely resulted in rapid exsanguination and shock, leading to his prompt demise after losing at least 20% of his total blood volume in a short period.