Archaeologists at White Sands National Park in New Mexico, while examining a 10,000-year-old track of human footprints, have made several fascinating discoveries. However, their findings have also unearthed a host of unanswered questions about the ancient mystery surrounding the relationship between humans and ice age megafauna.

These footprints, preserved over millennia, provide a rare glimpse into the lives of prehistoric humans. The ongoing research aims to unravel the interactions between these early inhabitants and the massive creatures that roamed the Earth during the last ice age. The discoveries thus far highlight the complexity of these ancient ecosystems and the potential roles humans played within them, but they also leave many questions about how these interactions influenced both human and megafaunal evolution.

Archaeology Detectives: Following Fossilized Footprints to Retrace Ancient Footsteps

The Alkali Flat in New Mexico, U.S.A., renowned as the world’s largest gypsum dune field, formed when a warming climate caused an ancient lake bed to shrink, leaving behind dunes and salt flats shaped by wind erosion. On these expansive flats, archaeologists have unearthed hundreds of thousands of human footprints dating back to the end of the last ice age, approximately 11,550 years ago. Alongside these human prints are those of many Ice Age megafauna, such as giant ground sloths, mastodons, mammoths, camels, and dire wolves, revealing a dynamic interplay between early humans and these colossal creatures.

In a 2018 article by Ancient Origins, researchers described ancient “ghost tracks” of these now-extinct animals. These tracks, visible only under specific weather conditions, suggested that humans had stepped into the prints of giant sloths as they pursued them. The evidence depicted a dramatic scene: the sloths, moving in large, flailing circles, would rise on their hind legs and sweep their arms to fend off hunters. When overbalanced, their knuckles and claws would strike the ground to regain stability.

However, recent evidence has significantly altered this narrative. While the precise details of these new findings are still emerging, they promise to reshape our understanding of the interactions between humans and megafauna during the last ice age. This new evidence may offer fresh insights into the behaviors, strategies, and movements of both humans and the colossal creatures they encountered, painting a more complex picture of life on the Alkali Flat during this ancient period.

Exploring the Longest Straight Track in the Ancient Americas

A new paper published in *Quaternary Science Reviews* significantly expands on initial observations from 2016, unveiling what is described as the “longest trackway of fossil footprints in the world.” According to PHYS.org, this groundbreaking discovery was made at White Sands National Park in New Mexico by an international team collaborating with the National Park Service staff. Unlike previous human footprint trackways, this one is notable for its impressive length, measuring at least 1.5 kilometers (0.9 miles), and its exceptionally straight path.

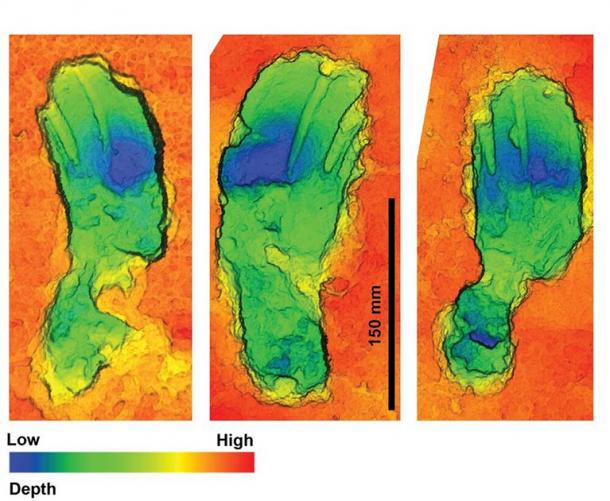

The linear nature of this trackway suggests that the individual did not deviate from their course by even a meter, demonstrating a determined stride. Even more intriguing is the evidence that the person retraced their own steps a few hours later. Just like detectives meticulously piecing together clues at a crime scene, researchers measured the depths and angles of each footprint along the track. This level of detail has allowed them to determine when the individual slipped or stretched, providing a remarkably accurate account of their journey.

These findings not only highlight the physical endurance and navigational skills of early humans but also offer a vivid snapshot of a specific moment in prehistoric time. The ability to track such precise movements underscores the advanced capabilities of current archaeological methods and enriches our understanding of human behavior during the last ice age.

Following Footprints in the Sand

This ancient trackway is composed of small fossilized footprints, which researchers believe were most likely made by a young woman or possibly an adolescent male. From analyzing this long, straight track, they determined that because the ground was wet and slick with mud, the individual maintained an exhausting speed of over 1.7 meters per second, significantly faster than the comfortable walking speed of about 1.2 to 1.5 meters per second on a flat, dry surface.

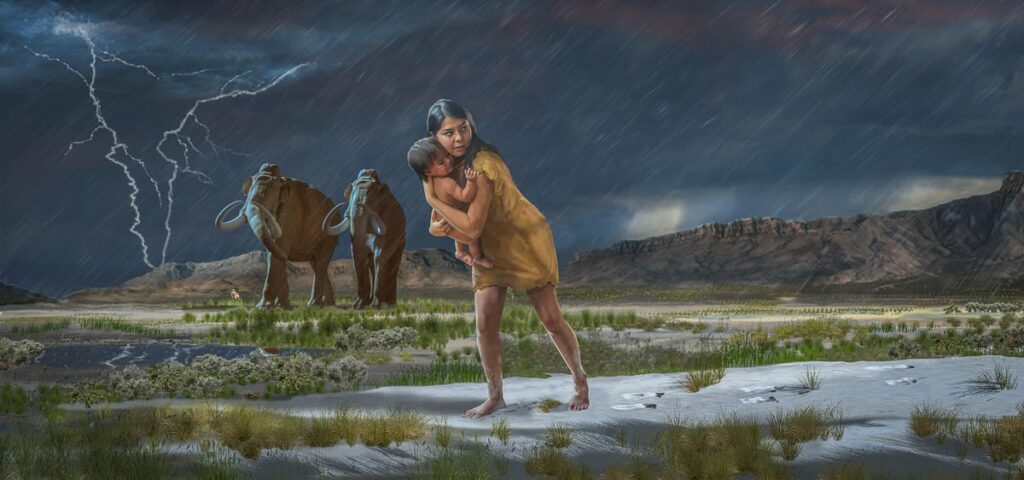

This discovery evokes a parallel to the popular allegorical religious poem “Footprints in the Sand,” where a person sees two sets of footprints, one belonging to God and the other to themselves. As the two pairs of prints become one, it signifies that God carried the person during their times of need. Similarly, returning to the Alkali Flat, researchers found tracks of a two-year-old child at several points along the outward journey. These tracks suggest that the child was set down periodically, possibly as the carrier adjusted them from hip to hip or took a moment of rest. However, while the child was carried outward, they were not present on the return journey.

This poignant detail adds depth to the narrative, highlighting the arduous conditions faced by early humans and the care they extended to their young. It also underscores the significance of the trackway, not just as a path etched in the mud, but as a record of human experience and resilience.

Readdressing the Sloth Incident

All of the above discoveries were derived from the shapes, depths, and twists of the footprints. The footprints on the outward journey were broader, likely due to the outward rotation of the foot when carrying a heavy weight. In contrast, the homeward journey footprints varied less in shape and were narrower, suggesting the person was no longer carrying the child. Additionally, evidence shows that a giant sloth and a mammoth crossed the outward trackway, as indicated by the return journey footprints overlapping those animal tracks.

This new evidence challenges the earlier story that depicted the giant sloth moving in “flailing circles on its hind legs, sweeping its arms to keep the hunters at bay.” Instead, the sloth tracks suggest that the animal was aware of the human’s passage. When the sloth reached the human trackway, it reared up on its hind legs to catch the scent, paused to trample the human tracks, and then dropped to all fours before moving off, indicating it perceived the human presence as a potential threat.

While this unique trackway has already provided deep insights into human movement 10,000 years ago, it also raises numerous new questions. What was the person doing alone, moving at such a speed, with a child, in a dangerous environment like the playa? The situation suggests that the child-carrying woman felt incredibly vulnerable in this wild and unpredictable landscape. Whatever her motivation, she made her journey, delivered the child, and returned, demonstrating remarkable determination and resilience.

This remarkable find at White Sands National Park not only enriches our understanding of prehistoric human behavior but also highlights the complexity of human and animal interactions during the last ice age. It serves as a powerful reminder of the enduring human spirit in the face of adversity and the intricate tapestry of life that once thrived in these ancient landscapes.