Despite the less-than-flattering descriptions and initial assumptions, the Soap Lady remains one of the most enduring specimens at the Mütter Museum of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia. For over 140 years, she has been on display, captivating visitors with her mysterious story. While much is known about how her body came to be preserved in such a unique manner, very little is known about the woman herself. Furthermore, scientific inquiry has challenged previously held beliefs about her, adding to the intrigue surrounding her identity and history.

Saponification to Mummification

Resting within the Mütter Museum, the Soap Lady resides in a wooden and glass case, evoking images of Snow White’s coffin from the Grimms’ fairy tale. Laid out on her back, her mouth is frozen in a silent gasp or a potential scream, subject to interpretation. Her hands rest gently on her legs, while her toes point slightly. Years of exposure to Philadelphia’s pollution have left her body darkened, and what remains of her hair forms wisps around her head. Her eyes, though they appear both open and closed, are actually shriveled and sunken.

An 1874 Delivery to the Mütter

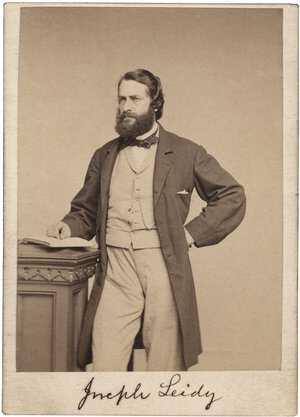

Dr. Leidy, a distinguished figure of the 19th century, was renowned for his diverse expertise as a physician, paleontologist, naturalist, and professor. As a Fellow of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia, he contributed numerous specimens to the Mütter Museum. In 1874, he presented the museum with one of two saponified bodies discovered in a Philadelphia graveyard. The female specimen, known as the Soap Lady, was received by the Mütter Museum, while the male counterpart went to the Wistar and Horner Museum, now The Wistar Institute at the University of Pennsylvania. Initially, Dr. Leidy provided information suggesting that both bodies belonged to individuals named “Ellenbogen” who died of yellow fever in 1792. The Mütter Museum accepted this narrative for over six decades until further investigation by Joseph McFarland revealed discrepancies.

McFarland embarked on a meticulous investigation into the life and demise of the Ellenbogens in Philadelphia. He encountered an immediate challenge with the surname. While the Soap Lady was simply designated as “The woman named Ellenbogen,” the label of the Soap Man at the Wistar Museum indicated “Body of Wilhelm von Ellenbogen.” The inclusion of “von” in a German name typically suggests noble lineage. McFarland set out to uncover any traces of these names in death records, church registries, ship logs, and other available documents. Despite his exhaustive efforts, McFarland failed to find any records of Ellenbogens, noble or otherwise, in the death registries of Philadelphia in 1792. Furthermore, there were no recorded deaths from yellow fever during that period. Even after scrutinizing published lists of thousands of yellow fever fatalities in 1793, McFarland could not find any mention of the Ellenbogens. Remarkably, there was no historical record of individuals with that surname in Philadelphia until after 1856.

McFarland’s investigation extended to the purported location of the cemetery near Fourth and Race Streets. Despite the presence of three German churches in the vicinity, he found that none of their cemeteries matched the description. Delving further into the archives of The College of Physicians’ library, McFarland made a revealing discovery that exposed Leidy’s deception. A handwritten receipt dated November 18, 1875, documented Leidy’s payment of two installments of $7.50 each to acquire the bodies from the gravesite. In the receipt, Leidy openly admitted to using “connivance” to obtain the bodies he sought.

Solving the Mystery of Mrs. Ellenbogen

Leidy might have initiated the acquisition of the saponified bodies, but he was not acting alone in these dubious dealings. Although Leidy was reimbursed by The College for his expenses related to obtaining the Soap Lady, it wasn’t until after his death that Dr. William Hunt shed light on the details of how Leidy obtained the bodies. Hunt, who served on the Mütter Museum Committee from 1865 to 1895 and was the acting curator during the Soap Lady’s acquisition, revealed the truth in an article published on January 16, 1896, in the Philadelphia Public Ledger:

The only instance I ever know of Dr. Leidy’s departure from strict truth was, to a medical man’s way of looking at it, a very amusing one. Some years ago he came to my house in quite an enthusiastic mood, and said: ‘Doctor Hunt, do you know that they are moving the bodies from a very old burying ground down town to make way for improvements?’ ‘Yes,’ I said ‘Well’ he went on, ‘two bodies turned into adipocere are there…They have been buried for nearly a hundred years, nobody claims them, and they would be rare and instructive additions to our collections.’ ‘Alright; [said Hunt] I shall be delighted.’

So Leidy went down to secure the prize. When he spoke to the Superintendent, that gentleman put on airs, talked of violating graves, etc.; so the discomfited doctor was about to withdraw. Just then the Superintendent touched him significantly on the elbow and said: ‘I tell you what I do, I give bodies up to the order of relatives.’ The doctor took the hint, went home, hired a furniture wagon, and armed the driver with an order reading: ‘Please deliver to bearer the bodies of my grandfather and grandmother.’ This brought the coveted prizes and the virtuous caretaker was not forgotten.

McFarland’s investigation may have solved one mystery, but it also opened the door to many more unanswered questions. With the revelation that the body was not Leidy’s grandparents, did not perish in 1792, and bore no relation to the name Ellenbogen, the Mütter Museum found itself in possession of the remains of an unidentified woman, adding to the intrigue surrounding the Soap Lady.